Moon Goddess Compendium

The Moon Goddess and her soft glow in the night sky has been equated with power for thousands of years. Her rulership of many aspects of magic and the lunar powers within theurgy (initiatory magic) practices, along with her worship, has been a recurrent theme for as long as history has been recorded; her legends are painted on ancient walls and carved into rock the world over.

Here is gathered the lore of the Western Moon Goddess in her many forms, myths and incarnations.

Ancient cultures across all geographical parts of the world honored The Moon Goddess, and many societies celebrated multiple. Feminine deities have recurrently been given the honor of representing the moon. Her phases correspond with the menstrual cycle, and have been likened to the growing up and aging process of women: the young virgin, the loving mother and the wise crone.

This compendium will bring together those stories to explore their magic. Several instances of feminine energy and power sadly will be seen to be reduced to evil in ancient myths, many edited and rewritten by dogmatic patriarchal authorities to suppress women’s sexuality and freedom, and simultaneously conceal allegorical aspects of the unconscious mind one is required to explore for true theurgical initiation and spiritual illumination. Behind these stories of darkness often lies a nearly universal archetype; a powerful yet gentle moon goddess that sagely controls the tides of the waxing and waning of the life cycle.

The Moon Goddess Lilith, an Inconvenient Independence

Perhaps the oldest moon goddess is Lilith, widely called goddess of the dark moon, often represented as a demon goddess, a purely carnal, sexual being.

The widely accepted myth of Lilith as a demon represents Western patriarchal society’s categorical rejection of female sexuality and individual autonomy. Her threat is her independence and refusal to obey men, unlike the more obedient Eve in the Biblical Garden of Eden, and her unwillingness to be controlled created discomfort at important points in history. Patriarchal rewritings of ancient myth occurred close to 3500 years ago, and tell us that she was condemned to lie with demons and monsters, making her own children beasts.

Hebrew mythology describes Lilith arguing with Adam over sexual dominance. She wanted the dominant position occasionally, and Adam would not allow it. Giving up out of frustration, Lilith uttered the Ineffable Name of God and was able to fly away into the air. Three angels were sent to bring her back to Adam by force, yet when they found her in a cave beside the Red Sea they could not convince her to return and were unable to force her.

Prior to this cultural shift, within the pantheon of ancient Sumerian gods and goddesses, Lilith was known as Lilitu, a great winged bird goddess. She was recorded in Sumerian myth as a young handmaiden to the Queen of Heaven and Earth, Inanna. Lilith brought the men from the streets into Inanna’s temple to engage in sacred sexual rites. Hebrew religion began to value women either as virgins or property of their husbands, so this old belief of the Sumerians needed to be changed, and the authorities found a way to change it into a tool of repression—exactly that which the Judaic Hebrew texts state that Lilith vehemently opposed.

Lilith was associated with the new moon. When children were heard laughing in their sleep on the night of the Jewish Sabbath or the night of a new moon, it was believed that Lilith was playing with them. Additionally, the Zohar, a collection of commentaries on the Torah, explains that Lilith, as a succubus, will visit a man sleeping alone on the night of the new moon and seduce him in his sleep. The resulting nocturnal emission will impregnate her with demon children.

The Zohar portrays Lilith as a malevolent force and was written around 2000 years ago, a time when sexual oppression was being written into governments and religions around the world, and well after patriarchal society had become the norm for many.

The true spirit of the moon goddess Lilith represents independence, fairness, equality and passion.

The Moon Goddess in Ancient Mesopotamia

Sumer and Babylon

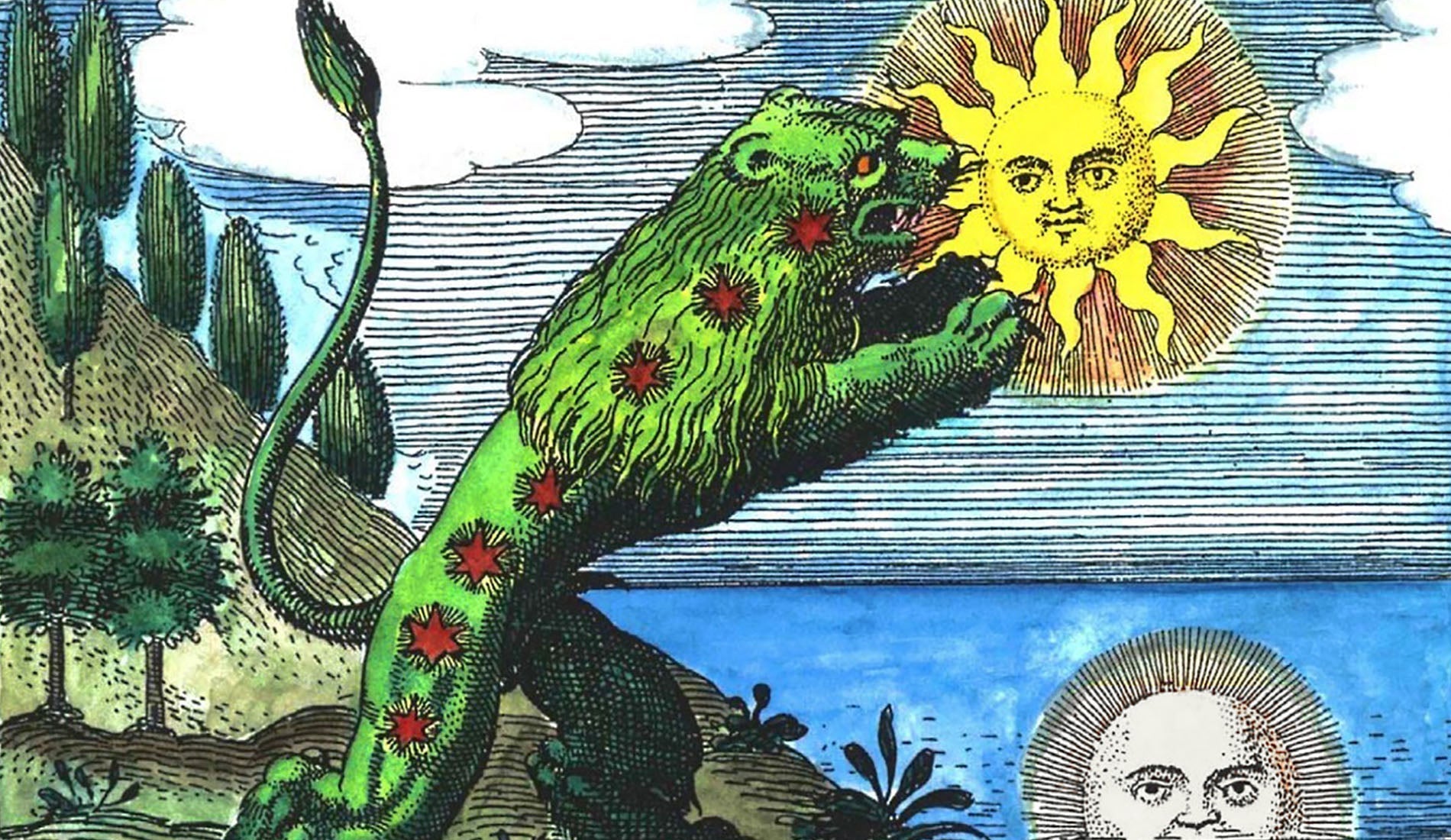

Ancient Mesopotamia spawned continuously evolving pantheons over its rich history. Ishtar, or Inanna, was the Babylonian goddess of the moon, love, fertility, passion, sexuality. She was symbolized with the moon, stars, lions and doves. She was the counterpart to the Semitic goddess Astarte, and may have previously been called Anunit from the same culture, who had association with the Evening Star.

Her cult was the most important in ancient Babylon, and for this reason she had many names, stories and aspects. Likely at different points these identities were all separate, but due to details becoming confused over time with oral retellings of the stories and the similarities, the different figures came to be known as one, most commonly Ishtar. The goddess is the progenitor of Venus and Aphrodite.

In a story more closely connected to the Inanna identity, the goddess learned of the grief of her sister Eriskegal, wife of the God of Death. Her sister lived in the Underworld with her husband. The god had just abandoned Eriskegal and Inanna wished to console her. The goddess was apprehensive about the visit; the two did not get along well. Inanna knowingly asked her servant to send help after her if she did not return within three days. Upon entering the Underworld, she came to the first of seven gates before reaching her mourning sister. The first gatekeeper demanded Inanna’s crown, and each subsequent gatekeeper demanded another article of the goddess before allowing her to proceed. When she finally reached Eriskegal, she was naked and stood humbly before her. In a fit of rage upon seeing her sister who had not visited her before this point, Eriskegal killed Inanna and hung her lifeless body on the wall behind her own throne.

After three days passed and Inanna had not returned, her servant approached Enki, the God of Wisdom for aid. The god created two small creatures from the dirt under his fingernails that were capable of administering the food and water of life should it be required. The creatures passed quickly and easily through the seven gates and reached the still-mourning Eriskegal with Inanna’s body mounted to the wall behind her. The creatures showed remorse for what happened with her husband and were able to comfort the grieving wife. Moved by the creatures’ kindness, she offered them any gift they desired. They asked for the body of Inanna to take with them. She agreed and the creatures were able to give the stricken goddess the food and water of life and her vitality returned. Eriskegal consented to allow the three to return to the world above, but only on the condition that someone be sent to take her place.

Upon returning, Inanna was enraged to find that a lover of hers, Dumuzi, had taken her crown and throne. She sent Dumuzi to the Underworld to take her place on the wall behind her sister’s throne. After some time passed and the goddess returned to tranquility, she felt remorse for sending her lover to the Underworld. She went after him and appealed to her sister for his release. They reached an agreement that he could return, but only for half of each year. Dumuzi became the God of Vegetation, and brings with him the seasons of spring and summer when he is allowed to leave the Underworld.

The identity of Ishtar may have some associations with the Christian celebration of Easter. These connections are disputed and even condemned by many Christian groups, calling Ishtar’s story demonic and likening her to the Devil. Since Ishtar was the goddess of fertility, eggs and rabbits were an obvious correlation, and they remain a symbol of the springtime celebration today in the Western world. Some scholars say that Easter is simply another form of Ishtar, though others suggest the origin is Ostara, the Saxon goddess of springtime and fertility.

Sadarnuna was a Sumerian goddess of the New Moon.

Sarpandit, a pregnant moon goddess, is the matron of the moonrise and reflection on the water. Her name is translated to “silver shining” from her Sumerian origins.

The Egyptian Moon Goddess

Isis had many names and possibly several identities have been combined into the single story of this goddess, like so many central deities across many pantheons. She was the “Mother of all Goddesses”, not just of the moon, but the earth, magic, life, death and rebirth. Isis was a creator and a destroyer. In addition to being a powerful deity, she was a loving wife and mother. The epitome of femininity, she spent time among other women, teaching them to bake bread, spin yarn, weave fabric and tame men so it would be possible to live with them. She was a well-loved amalgam of many lesser goddesses that preceded her in mythology, sometimes called the "Lady of Ten Thousand Names" and the basis for many to follow in many cultures.

At one point Ra, the God of the Sun held the greatest power, but he was uncaring and the people suffered a lot under his reign. Isis was able to trick him into revealing his source of power, which was the utterance of his secret name, and upon learning his secret name and saying it aloud, she gained the greater power and made the lives of the people and other gods and goddesses better by taking control.

In the most well-known and culturally influential story about Isis, she gives birth to a son, Horus, after piecing together her dismembered husband, Osiris. This is a notable birth, because Isis was able to locate all but one piece of her husband; his penis was never located, thus this myth is also the forerunner to Immaculate Conception. Osiris was also her brother. Another brother, Set, was so jealous of the couple’s love and power that he killed Osiris twice, and twice Isis was able to give him life again.

During early Christianity, followers of Isis did not want to leave behind their worship of the goddess, so they formed groups worshiping the Madonna, a mother figure holding the baby Jesus. Subsequent Pharaohs in Egypt were worshipped as Horus incarnate during their lives, and Osiris after they died.

Sefkhet, a moon goddess from ancient Egypt, was also the goddess of time, architecture and of the stars. According to some scholars, she was the wife of Thoth, the creator of the alphabet.

European Moon Goddesses

The Moon Goddess in Greek and Roman Tradition

The moon goddess Artemis was the granddaughter of Phoebe, daughter of Zeus, and Apollo’s twin sister. Immediately after being born, Artemis helped her mother, Leto, give birth to her twin brother, making her the protector of childbirth. She became the goddess of the hunt, purity, childbirth, both wild and tame animals, and of the moon. Represented by the waxing moon in triple goddess tradition, she is the embodiment of expansion, youth, excitement, innocence and a playful erotic aura. Her symbols are the bow and arrow, a waxing crescent moon, the deer and the bear.

In her Greek mythologies, the Olympian was known to hunt alongside her brother, who was jealous and helped his sister keep her purity, often with violence, even though the goddess found it abhorrent. Like Lilith, Artemis was not interested in obeying patriarchal rule. She asked her father for eternal virginity, which she was granted but had to continuously defend. In one instance, Actaeon, a hunting partner, saw her bathing and tried to rape her. In retaliation, she transformed him into a deer and her dogs killed him. The gift of eternal virginity also meant freedom from marriage, so Artemis was able to wander the sierras and wildernesses at her will, growing, learning and ever-expanding as the waxing moon.

Artemis was believed to protect those who displayed self-sufficiency and those who challenged gender roles. The Greek calendar was divided into three ten day periods for each moon cycle that began after the new moon. She is symbolized as the waxing moon, and is the first third of the triple goddess archetype. She is the youth, beauty and innocence of nature. She was the goddess of transition and was a guide to those struggling to survive, and in fact pushed people to thrive in difficult circumstances.

Selene, the Titan moon goddess, mature and motherly, is often shown in a chariot pulled by winged horses, wearing a crescent moon as a crown. She is called the eye of the night, the full moon, the round bright white of the triple moon goddess.

Mythology disputes her heritage, and even her identity apart from Artemis. In artwork, her face is more rounded and her stature is shorter and fuller than that of the young goddess. Also called Mene, Latin for 'month', she is associated with a woman’s monthly cycle, and thus with fertility. She was the only Greek goddess said to be the embodiment of the moon and not just a representation. Selene’s Roman counterparts were Diana and Luna, who had temples in the hills of Rome and whose mythologies are discussed in more detail below. Selene was also called Phoebe, who was one of the original Titans and grandmother of Artemis.

Her great love was Endymion, a beautiful, young shepherd prince. As the White Goddess traveled across the sky in her chariot, she saw Endymion asleep in a cave near the Lydian Mount Latmos. Since he was mortal and would one day age and die, she asked Zeus to send him into an eternal sleep so that he would stay young forever. In his enchanted sleep, he dreamed of holding the moon in his arms and as he did, he fathered fifty daughters with the moon goddess, who represent the fifty months that pass between each Olympiad. Another account said that since she loved Endymion so much, she asked Zeus to let the shepherd decide his own fate, and he decided himself to sleep eternally to retain his youth.

Like the bright white of the full moon, this goddess was honored with the color white. Pan, a lover, gave her a herd of white oxen, and the horses that pulled her chariot were white. She was celebrated with white candles and white roses. It was said that the rays of the moon fell upon sleeping mortals as Selene’s kisses fell upon her true love, Endymion.

Hecate the moon goddess, and goddess of magic, is the waning moon in Greek tradition; the third portion of the triple moon goddess archetype. Fertility and physical beauty have long left the crone, but she has the wisdom that can only come with age and long life. Some statues and illustrations of the goddess show her with three heads, all facing different directions. Some show her with dogs by her side and entangled with serpents while she carried a burning torch to light her path. Her myth originated from the Egyptian midwife goddess, Hekat. The Greeks emphasized her rule of the Underworld, and called her “Most Lovely One”, a designation for the moon.

Similarly in Roman tradition, Hekate or Trivia watched over the souls of young women who passed away before their prime. It is possible that a negative aspect was born this way; she was associated with angry, restless souls. In the Middle Ages, the Catholic Church condemned worshipers of Hecate, seers, healers, and midwives, and likened her myth to that of the Hag—the same stories told about Lilith roaming the earth at night.

When Hades pulled Persephone down to the Underworld with him, Hecate was called upon by the girl’s mother, Demeter, to aid her and comfort her in her anguish. She held the title Kourotrophos, meaning nurse. She was the nurse of all living things, a protector of childbirth and like Artemis, the goddess of transitions. By nature independent, she was compared and sometimes confused with the young Artemis and certainly is an older, wiser incarnation of the goddess.

Hecate and Artemis watch over change and transition that correspond with their moon phases. As Artemis grows, like a waxing moon, Hecate slows down and sheds that which has become unnecessary with the passage of time. Many people that engage in moon worship today invoke the moon goddess to help eliminate the parts of themselves that weigh on them and prevent them from advancing to a new growth state. The waning, slimming moon is the final stage of the moon trinity just before the dark moon, then rebirth.

A Roman equivalent of Hera, Juna, Juno or Juno Lucina was the goddess of the new moon, heavenly light, marriage, pregnancy and childbirth. She was the daughter of Saturn and the sister and wife of Jupiter. Etruscan culture called her Uni. In addition to the moon, she was the matron goddess of Rome and the Roman Empire. Alongside Jupiter and Minerva, they comprised the Triad on the Capitol and were worshipped as such.

Juna had three aspects: fertility, war or purification, and regality. The warlike aspect was more closely depicted in the Greek telling of her story. In this style, she was painted posing with a peacock while wearing an aegis, a goatskin shield or mantle. The month of February was very important in this culture, it was a period of change. Early spring posed threats of contaminants from the Underworld as Persephone was first permitted to emerge for the year. Juna was nearby to protect her land and people from these threats. February held meaning in politics too, and Juna was present there as well to oversee this time of renewal of political power. The Matronalia marked the end of the important month with a large feast for women. The goddess was represented veiled, holding a flower in one hand and a baby in swaddling clothes in her other arm.

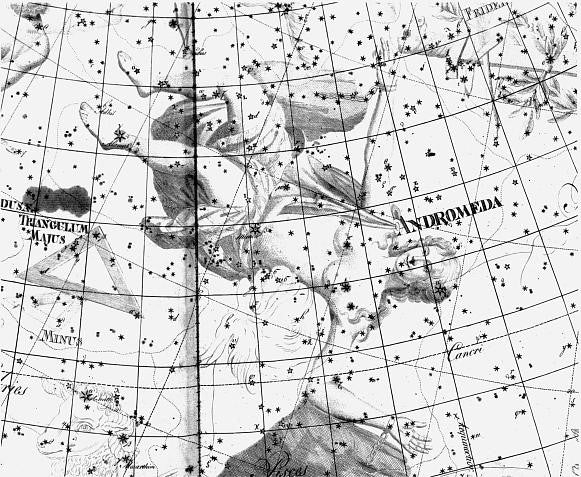

Like so many of the important female figures in the Greek pantheon, the princess Andromeda was associated with the moon along with the more famous part of her legend. In fact, the story of Andromeda is one that often comes to mind when one thinks of Greek mythology.

Her more commonly known concordance is with the stars, though it is believed that she was a pre-Hellenic moon goddess. Daughter of Cassiopeia and King Cepheus of Aethiopia, Andromeda was made to face the sea monster when her mother claimed that her daughter’s beauty was greater than that of the Nereids. They were a group of 50 sea nymph sisters under the care of Poseidon. Upon hearing the exultant statement made by Cassiopeia, the great sea god sent the monster Cetus to attack the Kingdom of Aethiopia. As a means of penance and an offering to the monster to spare the city, Andromeda was chained to a rock facing the sea. She was famously saved by Perseus, who defeated the monster using the severed head of the Gorgon Medusa. The monster was turned to stone on sight of Medusa’s dead eyes and the princess was saved.

Hand in hand with the freed Andromeda, Perseus approached the throne. He had made an agreement with King Cepheus to marry the princess after saving her and was ready to take his reward. Andromeda’s uncle, Phineus, was planning to marry her and was very upset to learn this. Perseus once again used the head of Medusa and killed Phineus. Though her parents did not want to keep their end of the bargain, Andromeda did, and they were married. As a reward for her honesty, Athena arranged for her to be placed in the sky as the constellation Andromeda.

In a nearby Thracian tradition, a cult moon goddess named Bendis has been closely associated with Artemis in Greek mythology and with Diana in Roman myths. She was most widely known for the night races named in her honor. The Bendideia were horse races where the jockeys carried lit torches and passed them to other riders, relay style, after a leg of the race. The games were very popular in the area, but the games and her worship in general did not stand the test of time. The poet Cratinus called her Dilonchos, either because she had two responsibilities, one of heaven and the other of earth, possibly because she carried two lances, or because there were two lights about her, one of her own and the other from the sun.

During a Roman occupation, an unknown number of the unique details of Bendis were lost and replaced with those of Diana or Luna. More widely known and worshipped, this Roman moon goddess also was authoritative over the hunt, animals, childbirth and women and was said to be a virgin goddess like others in this archetype. Diana could talk to animals and was said to be surrounded by maidens and deer as she passed through oak groves, sacred places to her. Having the connection to the moon made her unpredictable and susceptible to frequent changes of mood and heart. She carried the aspects of Hecate from Greek myth and thus was identified in later centuries with magic and lost souls, and was observed in places where three roads met as the triple goddess. To complete this association, Diana was strongly associated with fertility. In the temple of Artemis in Ephesus, there is an ebony statue of Diana, whose entire upper half is covered in breasts, symbolizing her role in fertility. She was storied to be a runaway slave, and was the protector of the slave and lower-class. Diana was celebrated in Rome and Aricia with a yearly festival for slaves.

Britomartis was the Cretan moon goddess that inspired the story of Artemis. She was the mistress of hunting and of the sea. Her monuments were found in the woods and along sea shores. The stories available come from Greek Historians, and at that point she was melded with others into the mythology of Artemis. According to the Greek folklore, Britomartis was a mountain nymph who, among others, cared for the infant Zeus when his mother hid the newborn from his father Cronus, who had devoured all of her previous newborn children. Later, the Greeks allowed Britomartis to keep her own identity, but she came to be known as a demi-god, daughter of Zeus and a favorite of Artemis.

Though she was known as the “good virgin” and “sweet maiden” and the Greeks popularized stories to fit that image, Minoan archeological finds show a darker side of the goddess. She is shown as a forceful hunter, sometimes with demonic features, wielding a double-handed axe and snakes and was followed by wild, brutish animals.

Britomartis’ association with the moon may have come from a story where she was pursued for nine months by Minos, who lusted after her. The huntress, like the moon goddess Artemis, was a virgin and desired to stay this way. Her escape from Minos was to jump from a cliff into the sea, but she was caught in a fishing net and made into a goddess by Artemis. The pursuit symbolizes the moon’s revolution around earth and final disappearance into the sea.

Achlys was a moon goddess, as well as the goddess of eternal night and sadness. She is described vividly in The Shield of Heracles by Hesiod, "And beside them [the Keres and the Moirai] was standing Achlys, dismal and dejected, green and pale, dirty-dry, fallen in on herself with hunger, knee-swollen, and the nails were grown long on her hands, and from her nostrils the drip kept running, and off her cheeks the blood dribbled to the ground, and she stood there, grinning forever, and the dust that had gathered and lay in heaps on her shoulders was muddy with tears." She gave birth to Chaos, and may have personified Misery. Achlys was the mist that fell before a person’s eyes when Death came for them.

Aceso or Akseso was a moon goddess and also a goddess of healing; however, she was known for the curing process, not the cure itself. She had an altar with Athena and Aphrodite in Epidauros. Her siblings were Aegle, Hygeia, Panaceia, and Iaso, and she was the daughter of Epione and Asclepius, who was the God of Healing.

Achelois was a minor moon goddess in Greek mythology. The Dodonian Oracle ordered sacrifices to be made to her in order to cure ailments.

The Basques Moon Goddess Tradition

Before being converted to Christianity in the Middle Ages, a group called the Basques worshipped a moon goddess named Ilargi in the Spanish and French countryside, bordered by the Pyrenees Mountains. There is evidence of Christian intervention as early as the fourth century CE but historians debate the period of Christian conversion among this group. Many of the translators working with Basque texts had no real knowledge of the language and relied on its similarity to Spanish and made an unknown number of mistakes in their transcriptions. Accuracy concerns aside, it is widely recorded that during this time in European history, an easy denunciation of any single person or a group of people was to adhere the label witch, as the translations of the Old Testament called for the condemnation of witches to death. Though the beliefs and practices of the Basques did resemble paganism according to old translations, it is difficult to know with certainty the true nature of this ancient people.

The moon goddess Ilargi Amandrea, daughter of Ama Lurra, the Earth Mother, was the moon embodied. She was considered to be the face of God, while the sun, Eguzki Amandrea (the Mother Sun), was God’s eye. Some scholars say that the Basque word for moon means “the light of the dead” and thus she illuminated the souls of the dead. The tradition tells us that before the Earth Mother had created a sun or a moon, the people of Earth were tormented by malevolent spirits in the darkness and they prayed for some kind of protection. To guide her people, she first created the moon, a soft white light in the dark sky to light the spirits as they traversed the land. The pale light somewhat protected people from the dark souls, but it was not enough. They pleaded again for help, and Mother Earth created the sun, a sister to the moon, and that was how daylight was created within their myth. The daylight created safety, but they were instructed to stay inside their houses after sundown; safety from the evil spirits could not be guaranteed by the moonlight alone.

The Basques believed that when people died, their souls walked on a rainbow to the moon and stayed in the safety of the moon goddess until they decided they wanted to return to the Earth to live another life. They did so in the form of rain drops.

The Etruscan Moon Goddess

An ancient city called Luna, presently central Italy, was known in the first century BCE for its wine and cheese. The cheese wheels were stamped with a crescent moon to mark its place of origin. The culture is steeped in deep mystery; most of what is known came largely from writings of the Romans and Greeks who simply were observing Etruscan culture. The myths are full of ambiguities and enough pieces are missing that painting a complete picture is impossible. The name of the city itself, Luna, may be Etruscan for 'port', and the city did have a very busy port. To further complicate the matter, the port had the shape of a crescent moon, another possibility for the name of the town.

Losna or Lusna was an Etruscan moon goddess most famously depicted on the back of a hand-held mirror in a scene with Praeneste and Amukes. She appears to be presiding over a boxing match between the two. A crescent moon hangs before her face and she rests on a staff. Losna was associated by the Romans to Diana, and the Greeks translated her name to Selene. Like other moon goddesses, she controlled the rhythm of the tides.

From the same region, we also have Aritimi. Also worshiped with the moon, she was the protector of the night, nature and fertility. She may have been the founder of the Etruscan town Aritie, today the Italian town Arezzo. Her mythology and name are very close to Artemis, and in fact the she later became accepted as the youthful Greek goddess of the moon and fertility.

Zirna was an Etruscan goddess of the waxing moon. She was often depicted with a half-moon around her neck, suggesting that she would have been honored at the second quarter phase of the moon. She had associations with Turan, the love goddess who is still recognized in modern Italian culture.

The Moon Goddess in Celtic Tradition

The name Arianrhod literally translates as ‘silver wheel’, and she was called the silver wheel that descended into the sea. Deemed a pale-skinned moon priestess from Celtic and Welsh tradition, she rode across the sky in a white chariot to watch the people she governed more closely. She was celebrated during the full moon and had a festival on December 2 of each year. In Wales during the second century CE, the Coligny calendar was developed. It measured the passage of time by night rather than by day, and the moon phases in stretches of five years. The Starry Wheel of Arianrhod was the measurement of relationship of the stars to the moon.

The Silver Wheel has a spinning and weaving connotation similar to the spider goddesses, and it was believed that Arianrhod's hand wove the tapestry of destiny and life.

The myth has the three aspects that are common among moon goddesses: the youthful Blodeuwedd, the flower maiden, the fertile caretaker as Arianrhod herself and the wise crone, Morrigu. She was the deity of the soul’s evolutionary cycles, and when people died, she took their souls on her ship, the Oar Wheel, to Emania, the moon-land of the dead. There she nurtured their souls between lives on Earth. The priestess of the moon was able to shape-shift into a large owl. This is a similarity to several other mythologies from different eras and traditions. In the Welsh culture, the sacred animal symbolized death, rebirth and understanding initiatory magic. As an owl, Arianrhod could see into a person’s subconscious through their eyes and was able to bring comfort to those who asked her with the soft beating of her majestic wings in the night air. The birch tree was sacred to her followers, it symbolized rebirth.

Another moon goddess from this tradition is Rhiannon. Her name translated to Divine Queen of the Fairies. Early in her life she was betrothed to a man who came from the same divinity as she did, but by whom she was revolted. She refused to marry him, upsetting the tradition that a goddess should marry one of her own kind. Instead, she fell in love with a mortal, Prince Pwyll, and appeared to him on an enchanted mound near his castle in the forest. People generally avoided these mounds, as they feared falling under a magic spell, but Prince Pwyll was unafraid. He fell in love with the goddess, mounted upon a white horse and dressed in gold that glittered in the sun, and after a substantial pursuit on which the she led the mortal prince, she proclaimed her love for him and her desire to marry him. He waited for his beloved Rhiannon at the enchanted mounds where they had met at the time they agreed upon and she led him and his group of the prince’s men into the enchanted, densely tangled, forests. Fearful at first to follow Rhiannon into the knotted thickets they had been warned as children to avoid, they were relaxed when they heard the songbirds that surrounded the goddess; they were sacred to her and had the skill to ease fears. Her father’s castle where the wedding and a large feast were held seemed to be made from sparkling crystal, with spires that stretched to the sky.

During the wedding feast, the man to whom Rhiannon had been betrothed was very angry and began to create a commotion. The goddess quietly turned him into a badger, tied him into a bag and threw it into a lake.

After the wedding, Rhiannon left the enchanted woods for the last time to be with her mortal husband and live in his family’s castle. Because she had married a human, she would never be able to return to her childhood home. The people in the kingdom admired her singing voice and her beauty, but after two years without having a baby, her ability to be the queen came into question. Fears were quelled when she gave birth to a boy the following year.

The morning after his birth, the baby was discovered to have disappeared. The governesses, fearful of punishment, made it appear as though Rhiannon had eaten her own baby by spreading the blood and bones of a puppy around the sleeping queen. She was punished for four years, made to stand at the gate of the city and confess her crime to visitors and offered them a ride on her back to the castle as if she were a horse. She so unflinchingly accepted her sentence that few people accepted her offer.

Her suffering came to an end when a man and woman appeared one day with her son, now four years old. They had found him crying in a field years before, and brought the boy to the town once they heard of the goddess being punished for eating her child and realized what had likely happened. It was suspected that Rhiannon’s once-betrothed was her baby’s kidnapper. The goddess’s honor was restored and she was allowed to return to her husband’s side. The people were so filled with shame for what they had done to Rhiannon that she was not able to be angry with them, rather showed forgiveness and compassion, and those, along with inspiration, are the values that have been attributed to this goddess of the moon.

Epona was a moon goddess with a relation to Rhiannon. Her symbol was a horse, and she was depicted sitting side-saddle on a horse who was eating from a fruit-filled cornucopia, a marker of fertility. She was worshipped from Britain to Rome and throughout Western Europe during the Iron Age. Her name means “Divine Mare” and she was celebrated in Rome on December 18. At one time, the mare was a symbol of fertility, and Epona was possibly a fertility goddess and later remembered only as a protector of horses. This is further suggested by the cornucopia often seen in her imagery. Similarly to Rhiannon, she was associated with enchanted birds but also with dogs. She may have a connection to the story of Lady Godiva.

There were three birds that accompanied Epona, and they were believed to grant life and death. Birds could travel between this world and the Otherworld at will, and they may have also represented fertility and love. When three birds were seen together, it was meant to be a visit from the triple goddess: the maiden, the mother, and the crone.

She was worshipped anywhere horses were common, and this is how her story became so prolific throughout the land. Anyone could become a Roman citizen if they served several years in the Roman army. Epona was introduced to the men of Rome and many other regions during their time spent fighting in Gaul, a pre-Christian, Celtic-French place of origin of the goddess. A deity for horses would have been perfect for soldiers who depended on the animals every day. There was not another in Roman mythology like this, so the story of Epona traveled and rooted everywhere the army did.

Aine was a goddess of summertime, especially midsummer, in Celtic tradition. She was the matron of fertility, love, wealth and sovereignty. She had command over crops, animals and agriculture. Many Irish families claim her ancestry.

It was believed that Aine could give and take away a man’s power, a show of her control of sovereignty. In a story that illustrated this aspect very clearly, the semi-mythological King of Munster, Ailill Aulom, came across Aine as he wandered her grassy hill at night, looking for a remedy for insomnia. When he saw the goddess, he lost his senses and raped her. For this brutish act, she bit off his ear. An Irish law stated that a ruler may not have any physical blemishes, and Aine’s punishment for the king rendered him unfit to sit on the throne. A similar story says that she is married to Iarl Gearóid, though instead of marrying her with her consent, he raped her. In this legend, she turns him into a goose or kills him, possibly both. The stories of the goddess were largely told in limerick form, many of which survive today. She was honored with the Midsummer Night feast.

The Cnoc Aine, or Knockainy Hill as it is known today, is the sacred hill where Aine was worshiped at least as far back as the Bronze Age, before the time of the Celts. There is a Neolithic stone cairn at the apex of the hill, and it was believed that Aine would come and go to Otherworld at this point, and it is the same hill where the king found her. On the night before large festivals, this portal was said to open and fairies from the Otherworld were able to influence people’s lives for good or bad.

Cerridwen was a Welsh mother Goddess, watching over fertility, creativity, the harvest, luck, inspiration, science and represented the moon. Creativity and inspiration came from her large cauldron of elixir that she stood over and stirred. The elixir was called awen, meaning divine spirit or poetic inspiration.

The goddess had a son, Afagddu, who was storied to be incredibly ugly. Cerridwen hoped to help him by brewing an elixir of wisdom. So great would his wisdom become that his appearance would no longer be his prominent feature. The brew took one year and one day to make, and required special herbs to be added daily at very precise times. Three magical drops of the potion was all that was necessary to attain great wisdom and clarity, as the young servant charged with tending the potion found out. The young man, Gwion Bach, accidentally in some versions, intentionally in others, spilled just three drops onto his hand and licked it off. The boy became a great magician in an instant and was able to elude the angry goddess. There followed a legendary pursuit, both the Gwion Bach and Cerridwen changing forms throughout the chase. They were a hunting hound chasing a rabbit, an otter swimming after a salmon, a hawk pursuing a sparrow through the air and ultimately the boy changed himself to a grain of wheat and hid on a pile of wheat on the floor in a grain barn. The goddess turned herself to a hen and ate Gwion Bach whole. She gave birth nine months later to Taliesin, who would become the greatest of all Bards.

She was also known as the goddess of witches and magic. The modern Halloween image of a witch standing over a bubbling, black cauldron under a full, bright moon comes from the myth of Cerridwen.

Ataegina or Ataecina, is from the traditions of the Iberians, Lusitanians, and Celtiberians of the Iberian Peninsula. The old Irish word adaig means 'night', but the Romans more closely identified her with Persephone, overseer of the changing seasons and rebirth, as suggested by the Celtic etymology of her name; at- means 'reborn'. She had sanctuaries in Portugal and Spain. Ancient art suggests that goats may have been sacrificed in her name.

Other Moon Goddess Traditions from Pre-Christian Europe

Sami shamanism was practiced in the region of Sápmi in northern Scandinavia in the Middle Ages. Their goddess of the moon was Mano. She was thought to be dangerous and unpredictable. She was honored at the new moon, especially during winter solstice, a time when followers were discouraged from making any sounds. Some traces of these oldest myths may have survived in traditional songs. There is a song about the birth of the world where a bird laid three eggs. One became the Sun, one became the Moon and the last became the Earth. Others suggest that there was a single egg from which everything hatched.

Finnish Goddess Kuu, means 'moon' and 'month' in the language, though more in-depth reliable information is hard to find.

The Moon Goddess in North America

Menily from the Native American Cahuilla mythology was a nukatem of the moon, meaning that she was one of the large creatures that existed in the far past, close to the time of creation. The majority of these creatures no longer exist today, according to legend, they became natural wonders like rainbows and mirages. They were prayed to and held in the highest regard, as a god or goddess in other cultures. Most nukatem were male, and Menily was special because she was female. She helped the Cahuilla people understand hygienic practices and helped them care for their long hair. Additionally, the nukatem was a great teacher and taught the people the importance of being happy. Women aspired to be like her as she had these qualities and great beauty.

The creator god, named Mukat, cast a spell on the Cahuilla people one night so they all slept very deeply. His intention was to play a joke on Menily. The god Mukat was known to be unpredictable and at times unkind. In a sleep trance, Menily rose and went to a lake and danced. She looked very ill as she danced. She awoke with the rest of people and was very sad for what had happened and wanted to leave them. She would not explain to anyone what had happened and why she felt so melancholy. Finally she wrote a song that expressed her feelings and the people understood. The great nukatem soon cast a deep sleep on the people as Mukat had done, and as they slept she left and took her place in the sky as the moon. The people despaired to wake and find her missing and a coyote was sent to look for her. Days later, her reflection was seen in a pool of water. Not understanding, the people begged her to leave the water and the coyote drank as much of the pool as he could. Though the water level was lowered, the water and her reflection remained and she laughed. Her people looked up to see her in the sky, and that is where she stayed to cycle month after month.

In Navajo tradtion, the Diné Bahaneʼ, or creation story, Yolkai Estsan was called The White Shell Woman because she was made from abalone. She and her sister, Estsanatlehi, known also as The Changing Woman and made from turquoise, were left on a mountain top after being created. The two were lonely after a few days and Estsanatlehi observed that the only movement they could see was the sun above and a waterfall below. She wondered if the two were people like they were and wanted to find out. She decided that she would wait for the sun to rise in the morning and greet it. She sent her sister to do the same at the waterfall. After their encounters, the sisters both learned that they had become pregnant, Estsanatlehi from the sun and Yolkai Estsan from the waterfall.

They both bore boys, named Monster Slayer and Born of Water. They were known as the Hero Twins and worked together to defeat the monsters of the world. Yolkai Estsan married Klehanoai the Moon and became the guardian of the east. Her sister the guardian of the west and married the sun.

In Navajo culture, the sun and the moon require their due respect. The moon should not be stared at, or it will follow the person who looks at it for too long. The sun can blind a person that stares for too long, and we know this this to be true.

The Pawnee Moon Woman was the mother of the first Pawnee man, and the father was the sun. There once was a great famine among the Pawnee people, and a young man fasted on a hill near the cave of the Moon Woman. She came out to meet him and gave him instruction to drink from a nearby pool of water. When he did, he saw reflected in the pool various women of all ages and at all stages of life, likened to the many and ever-changing moon phases. The Moon Woman gave the young man a bowl of corn to take to his people, and taught him ceremonies to draw buffalo out of her own cave. After giving these gifts to the young man, the cave and the Moon Woman disappeared. Afraid that they would be unable to summon buffalo, the people separated and became several bands of Pawnee across the land.

Hanwi is the Sioux moon goddess. The Sioux nation inhabited three large groups in the Midwestern United States, the Dakota, Nakota and the Lakota, the group most closely identified with the goddess. In the native language, Han means 'darkness' and Wi means 'sun'. Hanwi’s soft white light is said to be brighter than the sun because it pierces the darkness. Her people pray to her with moonstones and ask for just that, her light and healing to pierce the darkness that sometimes life can bring.

The Sioux creation myth says that Hanwi’s husband, Wi, the sun god, once allowed Ite, a mortal woman, to sit beside him at a great feast for the gods. The most beautiful of all women, though not more beautiful than the sun god’s own wife, Ite was jealous of Hanwi’s beauty and agreed to this plan to embarrass the moon goddess, cause a general disturbance and promote her own status. Her payment in exchange for the commotion was a physical beauty that would rival that of Hanwi. On the evening of the feast, Ite arrived early and took the seat next to the god Wi before his wife had a chance to sit. Enchanted by her beauty, Wi allowed it to happen. When Hanwi moved toward her seat and saw that it was occupied, she was humiliated and hid her face. The overseeing sky god and ruler Skan was very angry. As a punishment, he took Hanwi away from her husband and placed her in the night sky as the moon so the sun god would always be separated from her. In her shame for her husband’s carelessness, she continues to hide her face and turns it to the side, creating the phases of the moon.

Athenesic was also a moon goddess in several Native American tribes in north central North America.

The Haitian Moon Goddess

The Haitian moon goddess Erzulie is observed still today in Voodoo tradition. Originally from West Africa, the myth traveled to the Western world with the slave trade. In Africa, she was known as Oshun. Once her people and her story reached Haiti, she was called upon by women who were raped by their slave masters. It was believed that she was the only deity to hear the women’s cries and she was able to ease their pain and fear. The slaves were forced to practice Catholicism, and they did so in public but practiced their familiar religion in private. Over time, Catholic saints and African deities were blended, and the amalgam stands today. She is married to the sun god Legba, and is sometimes represented as Mother Mary wearing strings of pearls and surrounded by hearts. Her skin, apart from the Mary representation, is a rich dark color given to her by the heated encounters of the sun god.

Her color is blue, and she represents love, abundance and prosperity. She is called “The Loving One” and is called upon when one’s life needs to be organized and corrected. Peppercorns are used in her rituals; on her day of observance, her followers find ways to eat the food to honor and remember Erzulie, and the color blue is worn. In 1816, the mayor of Bermuda was given the statehouse to use for the rent of just one peppercorn, and it has been celebrated ever since with great pageantry to preserve the island’s good fortune under the goddess’s watchful eye.

Erzulie has a handful of aspects, first as the young lover, Mistress Erzulie, who has been compared to Aphrodite or Venus. Next is Erzulie-Ge-Rouge, the red-eyed crone who cries for the limitations of love and for the pain of loss. This aspect is related to release and purifying oneself from suffering. Erzulie-Toho is the ugly side of love, the part that looks for vengeance after hurt rather than healing. This aspect remains broken and seeks to hurt others and becomes sick from holding onto pain. There also is Erzulie-Dontor, who actively seeks to hurt others. This side is believed to be heterosexual, though she is the matron of lesbians. She is often shown as a scar-cheeked black virgin holding a baby. This part of the goddess is feared, and is called upon by women who are being abused or have been raped. She is also Maman Brigette, related to the goddess in Celtic tradition and is called upon to raise the dead. Across all of her aspects, Erzulie represents all human emotion.

Mesoamerica & the Moon Goddess

Xochhiquetzal, Xochiquetzal or Ichpochtli was a goddess in Aztec mythology for weaving, embroidery, fertility, beauty, a woman’s sexual power, promiscuous love and a protector for young women, pregnancy and childbirth. In the Nahuatl language, Ichpochtli means “maiden”. Xochiquetzal means “goddess of the flowering earth” and she is often depicted as a young beauty, adorned in fine clothing and surrounded by vegetation and flowers. She is said also to represent desire, pleasure, and excess and was the matron for makers of luxury goods.

She was married to Tlaloc, until Tezcatlipoca kidnapped her and she was made to marry him against her will. She was also married to Centeotl and Xiuhtecuhtli. She was the mother of Quetzalcoatl (the feathered-serpent god of wind and learning) with Mixcoatl, god of the hunt and also father to Coyolxauhqui, another moon goddess. Marigolds are sacred to the goddess and she inspired artists and craft workers.

She was celebrated every eight years in a festival where followers would wear animal and flower masks. The festival, also to celebrate artisans, was a place where people wishing for inspiration would dance around her statue and engage in bloodletting as a penance for their sins. She was impersonated in the Toxcatl festival, where she was married to a young man, lived in luxury for a year before being ritually killed.

Coyolxauhqui was the Aztec moon goddess. Meaning “golden bells”, or sometimes “face painted with bells”, Coyolxauhqui was the daughter of Coatlicue, earth mother and Mixcoatl, god of the hunt. Coyolxauhqui was the older sister leader to four hundred brothers, the southern star gods. They lived in Coatepec, a municipality still standing in Veracruz, Mexico.

One day while sweeping for penance, a feather floated down from the sky. She placed it on her breast. After she finished sweeping, the earth mother looked for the feather but was unable to find it. At this moment, she realized she was pregnant. Though it happened by a miracle, her children felt ashamed and thought their mother had dishonored them. Coyolxauhqui gathered her brothers and convinced them they should kill her for her supposed crime. They agreed.

Understandably afraid of what she knew her children were planning to do, Coatlicue was comforted by her unborn son, Huitzilopochtli. And as he promised, as her other children advanced to harm her, her son was born at that moment. He appeared a grown adult, bearing an eagle feather shield and arrows with turquoise points, his arms and legs were painted blue and he wore a feathered sandal on his right foot. A crown of feathers adorned his face, painted with diagonal stripes from the moment of his birth. He fought and defeated the brothers, and he attacked his sister with a snake until he was able to decapitate her.

To comfort his grieving mother, he cast the head of Coyolxauhqui into the sky to shine as the moon. Here at least, their earth mother could see and remember her daughter. Many of the brothers became stars in the sky alongside their sister.

In the same mythology, we find the story of Metztli (also Meztli or Metzi), from the Otomi people from the central plateau region of Mexico. She was the goddess of the moon, the night and of farmers. The myth is similar to that of Coyolxauhqui, and some tellings say that Metztli was a god rather than a goddess. The male aspect of this legend is Tecciztecatl, and their stories are similar and often intertwined. The figure has been called the lowly god of worms to make mention of cowardice; the goddess was meant to sacrifice herself to become the sun. Having been too afraid to prostrate herself in such a way, she shines only a pale light at night instead of lighting the sky during the daytime. She did ultimately immolate herself to become the sun, but it was after several fearful attempts, and another, Nanauatzin, was able to cast himself into the sky first. Shortly after his first sunrise, the deity Tecciztecatl-Metztli rose in the sky as well, as brightly as the first. It was decided there should only be one star in the sky of that degree. The moon goddess’s brightness was subdued by a rabbit, having the animal thrown in her face to lessen her light in comparison to the first sun. The “rabbit in the moon” is easily visible on the night of a full moon. Other cultures have identified this same shape as the man in the moon.

When the Otomi people reached the plateau region of central Mexico in the sixteenth century, they did not worship any type of deity, they only watched the skies. They built a sanctuary to the moon, who they called La Madre Vieja, The Old Mother, creator of the moon and earth. Her consort was El Padre Viejo, or The Old Father, the god of fire.

They counted the months from new moon to new moon, giving each month thirty days. The Otomi created a zodiac system with thirteen delineations, each cycle lasting 20 days. It is said to be more accurate than the zodiac system consisting of 12 delineations that most westerners observe.

Called the Queen of the Night, Awilix was the Mayan moon goddess. There is some account that Awilix was a male deity, but there is enough evidence that the honored was female for her to be largely accepted as a goddess. Her mythology may have derived from that of C'abawil Ix, an older Mayan goddess of the Underworld, sickness and death. She may have had an association with the eagle and the jaguar, as they had connections with the moon and the night. Her calendar day may have been ik' ("moon"), in the 20 day month calendar, similar to that of the Aztecs. Together with Tohil and Jacawitz, Awilix was one of three main deities of the K'iche'-Mayan people. Her name may come from the language’s word for swallow, the bird. The goddess makes several appearances in the Mayan Popul Vuh, a very important text for the Mayan people. The goddess was believed to have had wells of healing waters on the moon which she sent to the earth as rain showers. She represented fertility and governed when people on earth could become pregnant. Similar to the Aztec lunar mythology, Awilix is sometimes represented with a rabbit as a companion.

A similar myth within the pantheon is of Ixchel. She may have been an incarnation of the goddess Awilix, and some scholars argue that the myths are one in the same. Ixchel lacks the sexuality of Awilix. Some state that Ixchel was created as a way for Spanish conquistadors to Christianize the Mayans by blending the two sets of beliefs, making Christianity more palatable to the people in this new world over whom they desired control. Interestingly, Ixchel was also the goddess of weaving, and though is still celebrated as such today in parts of Guatemala, she is generally worshipped as Santa Rosa, the Catholic matron of weaving.

Her associations to the moon, femininity and fertility are in place, but to a lesser degree to Awilix. She also offered healing and comfort to humanity, especially to women during menstruation and childbirth. Opposingly, Ixchel also held the power to bring floods, which of course also brought death and destruction, and water-borne bacteria and their related illnesses. Her name is possibly translated as “Lady Rainbow”, and though it carries a pleasing sound, to the Mayans, rainbows were bad omens, so a “Lady Rainbow” would be a bit ominous.

Oral history of this goddess’s stories has not survived, and her myths have to be largely guessed based upon the artwork in which she appears. One such supposed story of the moon goddess described her as almost too beautiful, with opalescent skin. She easily held the attention of the gods, except the sun god, Kinich Ahau. He was immune to her beauty and did not notice the goddess. Ixchel was smitten with him and began to follow him around. In doing so, she caused great floods from the ocean’s tides rising too high and losing their predictable pattern. She did not notice the havoc she was wreaking upon the earth as she fought for the sun god’s attention. Finally, he notice her, but it was because of her magnificent weaving. They became lovers and she bore four sons, all jaguar gods that could move through the night unseen. Kinich Ahau was jealous and abusive, constantly accusing Ixchel of having an affair with the morning star. After realizing that the sun god would never change, she left in the night, and maintained a distance from the sun by making a home of the night sky as the moon.

A related moon goddess in the Aztec tradition is Mayahuel. She was the goddess of pulque, a natural alcoholic drink made from the sap of the maguey plant. Their connection is the rabbit. Mayahuel is often depicted with several breasts, the myth says 400, to feed her 400 children, called the Centzon Totochti, or 400 rabbits. Because of this connection, vessels for drinking pulque in a ceremony often share a rabbit motif or a yacametztli, or crescent moon symbol.

Drinking pulque ceremoniously was thought to bring a person closer to the divine, and in fact give the drinker a bit of divine nature themselves. A person destined to become a human sacrifice was given pulque, and in modern-day Mexico, the drink is still believed to have transcendental qualities. It is still used in ritual. Traditionally-made pulque is available to buy on street corners by the half liter for pennies, ladled from large cooking kettles resting on ice. It can be found also and in pulquerias, sometimes resembling a typical bar and sometimes just an empty building space with seats. It is a point of pride for Mexicans, along with its history and mythology.

Zäna, the Queen of the Night, in Otomi tradition was the Moon in ancient Central America. They called her the Old Mother and she cared for both the Moon and Earth. The Old Father, the god of fire, was her husband. The thirty days between new moons was counted as a month in Otomi culture.

The Moon Goddess in South America

In the pre-Columbian region in present-day Bogota, Colombia, indigenous people of the Cordillera Oriental highlands of the Andes practiced an ancient religion known as Muisca. In this pantheon, a goddess, Huitaca, was worshipped in the name of art, music and dance, witchcraft, sexual liberation and the moon. This lunar goddess has strong associations with Chía and Bachué, mother moon goddesses of the same tradition. She valued a life of drunkenness and excess. The god of education, Bochica, despised this lifestyle and turned the goddess into an owl (some myths say she was turned into the moon), an associated animal of moon goddesses from all over the world. His condemnation of her behavior and lack of a stringent morality caught on among the people, who also were quick to condemn her and her excess. To this day, her stories also label her as the goddess of evil. Ironically perhaps, a similar myth of Chía is the story of the god Bochica’s wife, and she was truly evil.

Rather than an iniquitous lifestyle, Huitaca wanted to teach people to live in harmony with each other and with nature and to enjoy the pleasures of life. Her punishment to live her life as the moon or as an owl meant that she was limited to the nighttime and not allowed to enjoy the light of day. Not surprisingly, there is some evidence that the carefree goddess was labeled evil by Spanish forces wishing to gain rule over the people in this region. Her habits may have been exaggerated for history as they were condemned. As evidenced from mythological interpretations dating from the sixteen century in numerous sections of the world, feminine sexuality and power were demonized as a manipulative way to turn a people’s belief system on its head and take calculated control.

Today, natives to the region in Colombia regard the story of Huitaca as one of happiness and freedom and have been able to largely separate the outside misunderstanding and hasty judgement from outside cultures. Aside from her connotations to misdoings, still occasionally talked about by grandparents passing down the oral history to their grandchildren, Huitaca is remembered as a lover and symbol of nature, music and art.

In Peru, the Incas ruled their empire in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, finally being defeated in total by Spain in 1572. The Incas had many gods and goddesses like other religions from this area of the world at that time. Their moon goddess was Quechua Quilla, or Mama Kilya as named by the invading Hispanics. She was the daughter of the founders of the Incan culture, and married to her brother. Their daughter, Mama Ocllo, became the goddess of fertility and taught women to spin thread. She was the protector of women, and the goddess of marriage, the menstrual cycle and of fertility. She was said to be unearthly beautiful and her temples were cared for by women. Divination could be conducted in her name by watching the shadow of a tree pass over the ground while a person thought of a problem in need of solving. With meditation, Mama Quilla would provide the answer.

The Incas explained the dark spots on the moon were from a fox that fell in love with the moon because of her beauty. The fox ascended into the sky and Mama Quilla hugged the fox so closely that the dark spots appeared on her surface. Lunar eclipses were terrifying events because the Incas believed that the moon was being attacked by an animal. They feared that if she were overcome in an attack, their world would become dark. During an eclipse, the people would throw weapons and shout at the moon in an attempt to scare away the animal they thought to be attacking Mama Quilla. The Spanish took advantage of their fear and gained the respect of the Inca when they were able to correctly predict the lunar eclipse cycle. Even after conversion to Catholicism, the practice continued and Mama Quilla was still observed as a moon goddess for some time.

Auchimalgen is a Chilean moon goddess. Her themes are blessing and protection, and her symbols are silver bowls filled with water and white flowers, the color silver and anything related to the moon. She was believed to protect her people from problems that would arise in the future and averting unseen disasters. Her husband was the sun who blessed the land with daylight, while she provided soft inspiration through the darkness. She was worshiped by the Araucanian Mapuche, presently in south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina.

For the Araucanian Mapuche, Auchimalgen was the only deity that cared for the human race, all of the others had poor intentions. They believed that the goddess (perhaps the moon) would turn red when someone important was going to die.

Yemanja or Iemanja is considered Brazil’s sea spirit and the spirit of moonlight. She is still celebrated today, as there is a meeting between the Catholic Nossa Senhora dos Navegantes (Our Lady of the Seafaring) and the goddess. Her roots are African, and her legend has reached shores all over the world.

On February 2 each year, people meet at the sea shore at dawn for offerings to be made to the goddess in Rio Vermelho. Women’s items generally related to vanity are collected; lipstick, mirrors, perfume and flowers are collected in large baskets. Fishermen take the baskets to sea and make the offerings to the goddess. Street parties follow. In Salvador, Bahia, the goddess is celebrated on December 8 with the Festa da Conceição da Praia (Feast to Our Lady of Conception of the church at the beach) to celebrate the saint and the moon goddess. In Rio de Janeiro on New Year’s Eve, thousands gather at the beach to welcome the New Year. Celebrants throw white flowers and other offerings into the sea with the hope that the goddess will grant their wishes for the year ahead.

In Haiti, the same is worshipped as Yemaya or Agwe, a Voodoo moon goddess, also a goddess of the sea and protector of women and children, the bringer of seduction and wealth. Yemaya is related to the mermaid spirits of Lasirenn. She oversees the surface of the sea, where the most life is found. She is balanced by Orisha Olokin, the god who presides over the depths of the ocean. Her first gift to humans was a sea shell. When a person holds a shell to their ear, the sound heard is believed to be her voice. She is depicted as a mermaid or a beautiful woman with pearls streaming from her hands. She sometimes is shown wearing a blue and white skirt.

The Tupi people lived in present-day Brazil 2900 years ago. Known for cannibalism, they eventually migrated south to occupy the Atlantic Coast. When the Portuguese arrived to South America in the sixteenth century, they estimated the Tupi population to be around a million. Jaci was the goddess of the moon, lovers and crops, protector of reproduction. She was celebrated with feasts at the new and full moon. Ari was also associated with the moon, but very little exists aside from her name.

Predating Mama Quilla in the Incan tradition, there was Ka-Ata-Killa, a moon goddess from the area around Lake Titicaca, though little yet is known about her myths.

Conclusion

There are surely other instances of the Western moon goddess that are not yet included in this compendium. Their absence is merely a time constraint which may be remedied in due course of time. Likewise, there are many beautiful myths of the Eastern moon goddess across countless cultures, and though the focus in this post is Western, heartfelt acknowledgment is given here to all moon goddesses, named and unnamed, known and unknown, both East and West, across all time and cultures. They are the guardians of magic and gatekeepers of the lunar veils concealing deeper levels of reality—levels perceived through Illuminatory Seership—levels that pierce the Otherworld, explored by the spiritually courageous, and feared by those without the courage to explore.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_White_Goddess

http://www.mountainastrologer.com/standards/editor's%20choice/articles/lilith_hunter/lilith.html

https://sacredsites.com/europe/malta/temples_malta.html

http://www.theoi.com/Thrakios/Bendis.html

https://journeyingtothegoddess.wordpress.com/2012/02/29/goddess-lilith/

http://judaism.about.com/od/jewishculture/a/Where-Does-The-Legend-Of-Lilith-Come-From.htm

http://www.greekmythology.com/Olympians/Artemis/artemis.html

https://loveofthegoddessblog.wordpress.com

http://basquemythology.amaroa.com/antiguas-divinidades

http://www.thaliatook.com/OGOD/losna.html

http://www.crystalinks.com/etruscans.html

http://www.thewhitegoddess.co.uk/the_goddess/arianrhod_-_goddess_of_the_silver_wheel.asp

http://www.goddessgift.com/goddess-myths/celtic_goddess_rhiannon.htm

https://feminismandreligion.com/2013/03/13/rhiannon-goddess-of-birds-and-horses/

http://www.pantheon.org/articles/n/nukatem.html

http://www.lowchensaustralia.com/names/native-american-goddesses.htm

http://www.bsu.edu/classes/magrath/205fall/dakota.html

https://www.inside-mexico.com/the-legend-of-coatlicue-coyolxauhqui/

http://www.onereed.com/articles/moonweek.html

https://www.azteccalendar.com/god/Mayahuel.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sami_shamanism

http://herosjourneyrpg.blogspot.mx/2015/03/goddesses-of-above-and-below.html

http://cuantoconocesdechia.jimdo.com/origen-e-historia/mitos-leyendas/

https://journeyingtothegoddess.wordpress.com/tag/mama-killa/

https://www.naic.edu/~gibson/pleiades/pleiades_myth.html

https://journeyingtothegoddess.wordpress.com/2012/04/22/goddess-ishtar/

https://inanna.virtualave.net/ishtar.html

http://www.ancient-origins.net/myths-legends/britomartis-original-virgin-huntress-003537

http://www.classics.upenn.edu/myth/php/tools/dictionary.php?regexp=BRITOMARTIS&method=standard

http://www.greeka.com/greece-myths/perseus-andromeda.htm

http://www.goddess-guide.com/moon-goddess.html

http://themodernantiquarian.com/site/7737/cnoc_aine.html

http://www.ancient-origins.net/myths-legends-europe/celtic-goddess-epona-rode-swiftly-across-ancient-roman-empire-002641

http://www.angelfire.com/journal/ofapoet/epona.html

http://www.crystalinks.com/aztecgods.html

http://atheism.about.com/od/aztecgodsgoddesses/p/TlalocAztec.htm

Smith, William. (2007). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. I. B. Tauris.

George, Demetra. (1992). Mysteries of the Dark Moon, The Healing Power of the Dark Goddess. HarperCollins.

Kvam, Krisen E. et al. (2009). Eve & Adam: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Readings on Genesis and Gender. Indiana University Press: Bloomington.

Thomson de Grummond, Nancy. (2006). Etruscan Myth, Sacred History, and Legend. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Lynch, Patricia; Roberts, Jeremy. (2010). Native American Mythology A to Z. Chelsea House Publications.

Stookey, Lorena Laura. (2004). Thematic Guide to World Mythology. Greenwood.